This post may offend some personal injury lawyers. But maybe it will also cause some introspection and inspiration.

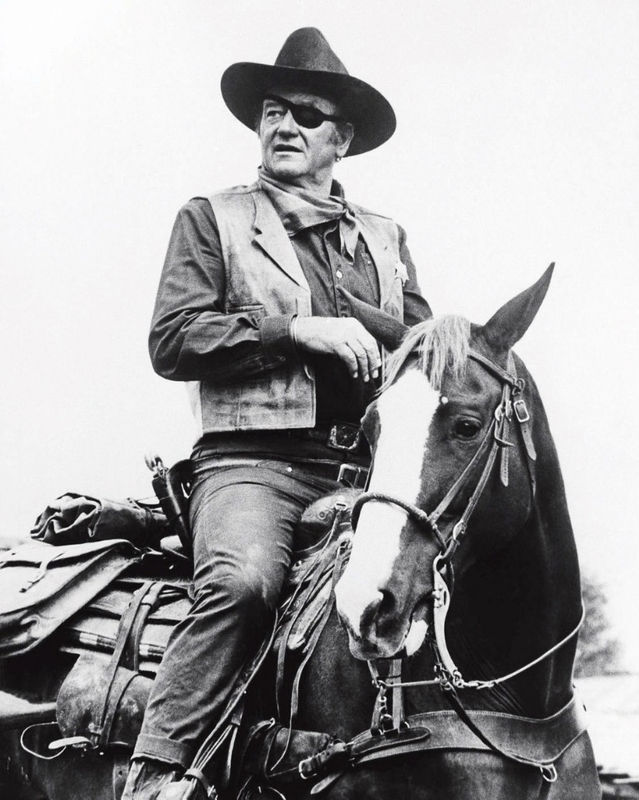

As a profession we are constantly being reminded about the importance of A2J (Access to Justice) for low income folks. We are forcing newly minted attorneys into Pro Bono work touting it as a rite of passage, an honor and a privilege to give back for earning this license. Those charged with a crime are given public defenders at no cost to protect their rights. But what about hope for plaintiffs in difficult personal injury or medical malpractice situations? What if doing pro bono is not defined as the lawyer foregoing a fee, but taking on cases that challenge an attorney to swing for the fences even if the odds are slim there will be a financial return; where the overarching goal is hopefully helping to right a significant wrong and maybe prevent future wrongs? What about taking on that difficult personal injury or medical malpractice case, the ones that fewer and fewer lawyers have the caring or courage or fortitude to take on because the odds are against victory, though should they be victorious, there is tremendous financial reward plus the gratification of helping someone? What about that plaintiff who needs a real cowboy?

Where are the personal injury cowboys?

They are a dying a breed. I’m learning this the hard way even though I’m not a plaintiff in any matter. But I’ve known a few cowboys in my time and recently one of the greatest suddenly passed away. He was a legend, the lawyer’s lawyer. The lawyer you referred to when the case was truly hard but extremely worthwhile because, if won, it was financially rewarding, could have lasting impact and change law. Cases that require brilliant strategy, creativity, incredible skill and faith in yourself that you are fighting the righteous fight even though the odds are against success.

When he passed suddenly he had 75 cases that all fit this description. These cases were his raison d’etre. Each required nuance and brilliance and sheer chutzpah; more compassion for the plaintiff than caring for the statistics of success. I volunteered to help the trustee go through some of his files to place these cases with other attorneys as he actually was a solo. They were in various stages of preparation, some the eve of trial. And while other lawyers were banging down the door to cherry pick the easy or easier cases, the tougher ones, the ones with such egregious harm to the plaintiffs perpetrated by outrageous behavior by the defendant, they were left languishing, the plaintiffs desperate. Lawyers were curious but without relatively easy dollar signs for minimal work, passed on them.

One case in particular upset me. The case was more than 3 years old. A 22 year old young woman was killed due to a blatant highway defect. The lawyer had 90% of the case done, excellent experts and strategically it was set up perfectly. However, when you sue a municipality it requires a finding of 100% liability. Not impossible to win but you must be very skilled and very courageous and understand completely how to effectively deal with any obstacles. It is a case that requires an incredible level of caring and commitment to achieve success. It also requires extraordinary trial skills because a case like this seldom if ever settles. This lawyer had those skills in spades and he believed in getting the family of the decedent justice and punishing the municipality for their blatant disregard of their responsibilities.

When I contacted personal injury lawyers I believed had the star power, the resources and the track record to review the case, I ultimately was met with the same reaction: they were attracted to the case value, the story, the challenge, the fact there would be minimal investment for maximum reward should they prevail. However, when they plugged it into their secret sauce-making machine to spew out the likelihood of success they would end up passing. It was never about the plaintiff and their loss. It was always their odds of prevailing. In essence, the rationale was that unless they could hit a home run, they weren’t picking up the bat. I even got into a lengthy discussion with one attorney who, after analyzing the case, was giving it strong consideration because he had a moment of humanity and said, ‘we can’t take on every case always expecting to win. We have to be willing to take on the cases we have a serious chance of losing if for no other reason than to fight the fight for the injured.’ It was a personal injury attorney’s version of pro bono. He ultimately declined because 1) all his partners told him he was absolutely crazy to touch it, and 2) by the time he could plug it into his trial schedule it would be two years down the road. My guess is the second excuse was to cover the pressure from his partners. As I write this, this poor plaintiff’s case is still languishing as more rock star lawyers pass on the case preferring the sure(r) thing.

In another case, a medical malpractice case, a doctor failed to diagnose a brain tumor. The brain tumor was ultimately discovered when the man suffered facial paralysis, was slurring his words and landed in the hospital forcing immediate surgery. Unfortunately, the discovery came one month after the statute of limitations ran (which can be overcome but it would require good lawyering). A rock star law firm known specifically for this work and dealing with statutory issues declined because ‘we ran it through our proprietary calculus and the odds of winning stand at 20%. For this reason, we have to pass.’ Yes, they have a proprietary system for calculating odds of success and this is their specialty. What about the plaintiff’s catastrophic and ongoing injury and keeping this doctor off the streets so he can’t harm another patient? I subsequently learned that as this firm grew, they only took on cases of high value with 75% chances of winning.

Before personal injury lawyers respond to this post by saying that in order to stay in business they have to make sound business decisions on how to allocate their resources, that calculating a likelihood of success plays into making good business decisions, and it’s unethical to hold out false hope to plaintiffs, and you can’t serve all injured parties, etc., etc., you are preaching to the choir. At Solo Practice University we teach lawyers how to run legal services businesses so you can stay in business. But this is not what this post is about. Many solos, by definition, can’t take on these types of cases because of the very nature of their practices and the limits on their personal time and resources. Quite frankly, we’re not talking about solos here because it would be the extraordinary solo who can take on cases like this without help.

We’re talking about lawyers, in general. Lawyers who have the clout and the resources to not have every case they take on be a guaranteed win. Have we gotten so far away from the mission of lawyering, especially in the personal injury practice area, that we fail to see serving clients isn’t always about the guaranteed win but also about getting plaintiffs their day in court, too? And, yes, in contingency cases you are usually fronting money, oftentimes borrowing against a line of credit, and promising that if there is no win there are still no costs to the plaintiff. So, yes, you have to calculate the financial risk versus the potential for reward. (But then how often do you take on sure things, put in minimal work and get a nice pay day. Can’t a portion of that be banked for the not-so-sure thing?). But when did lawyers stop swinging for the fences on bona fide cases simply because the odds are not in their favor? Especially those who pride themselves on taking these risks, brag about their multi-million dollar wins on their websites to attract clients, have always held themselves out as champions of the greater good. (And, for the record, the majority of expenses were already incurred in the first case so there was little left to invest against a potential ‘telephone number-sized reward’ with everything set out for a likely positive jury verdict. )

The lawyer who died was one of the last of the great cowboys. And every lawyer I spoke to could only say the greatest things about his larger than life skills. That he was ‘one of a kind’. You could even tell they aspired to his level of genius, envied his courage as well as his $10s of millions in plaintiff verdicts over the years. But not one was willing to pick up his hard cases. Not one was able to come up with a reason why that didn’t sound weak and mercenary. Not one looked to try and fill his shoes. It just made me very sad. Sad for all those plaintiffs who won’t get their day in court because lawyers who are both professionally and financially able forgot why they went to law school in the first place.

Comments are closed automatically 60 days after the post is published.