If the message is important, it’s worth sending a certified letter or getting a signed acknowledgment. It can be costly if you are unable to confirm that the information has been received.

If the message is important, it’s worth sending a certified letter or getting a signed acknowledgment. It can be costly if you are unable to confirm that the information has been received.

Attorney Joseph Shaffer learned this lesson when he represented Mark and Cynthia Peck in a medical malpractice claim related to the birth of their daughter, Madison.

In August 2006, two days before her scheduled caesarean section, Mrs. Peck woke up in extreme pain. She was experiencing an abruption of the placenta. When Mrs. Peck called her obstetrician’s office, they discouraged her from coming in. Mrs. Peck insisted that she needed to be seen. After she arrived at the office, Mrs. Peck spent nearly forty-five minutes in the waiting and exam rooms before being seen. After a brief exam, the doctor recommended that she drink water and walk the hallways of the office. She continued to experience terrible pain and was eventually transferred to the nearest hospital. Approximately five hours after Mrs. Peck’s initial call to the doctor, Madison was delivered. Madison had significant brain injuries due to lack of oxygen and was later diagnosed with cerebral palsy and developmental delays.

The Pecks believed that Madison’s brain injuries were caused by delays and negligent care on the part of her obstetrician. In December 2006, they consulted with Shaffer, an experienced medical malpractice attorney, about their claims. Shaffer began collecting Madison’s medical records. He sent the file to a nurse who advises attorneys on medical issues in potential malpractice cases. He communicated regularly with the Pecks. During one conversation, Shaffer suggested to the Pecks that it might be best to wait until Madison reached preschool age before having a physician review the case, so they could learn more about her development and the potential damages.

Consistent with this plan, in 2008 Shaffer asked two well-respected physician experts to review the obstetrician’s care. The initial opinions were not good. Both potential experts advised Shaffer that it would be extremely difficult to prove causation because it was impossible to pinpoint when the injury occurred. They explained that the abruption most likely occurred early in the morning when Mrs. Peck began experiencing pain, and this could suggest that Madison was already suffering from a lack of oxygen when Mrs. Peck called the office. According to the experts, there was credible evidence that Madison would have had permanent brain injuries even if Mrs. Peck had been immediately sent to the hospital for delivery. Based on these opinions, Shaffer concluded that he could not make out a malpractice case against the obstetrician.

In September 2008, Shaffer contacted the Pecks by phone and advised them that he would not be able to represent them in their malpractice case because of the causation issues. He followed up with a letter, confirming that he was disengaging from the representation. The letter informed the Pecks that a three-year statute of limitations would apply to their claim to recover medical expenses. This statute of limitations would not run for approximately eleven months, so the Pecks had time to consult with another attorney if they wished to pursue the claim. Shaffer felt comfortable that he had discharged his duties to the client, and he closed the file.

In May 2012 – two and a half years later – the Pecks called Shaffer to inquire about the status of their case. They denied ever receiving a call or letter from Schaffer informing them that he was terminating the representation. They recalled discussions with Shaffer about a “wait and see” plan that involved monitoring Madison’s development until age five so they could better determine the extent of her developmental delays and impairments. They had no idea that their claim would be barred by the statute of limitations after August 2009.

Shaffer pulled his file to retrieve a copy of the disengagement letter. The copy he found was an unsigned draft that was not printed on letterhead. Shaffer was confident he had dictated the letter and given it to his assistant to be finalized. The Pecks were equally confident that they had not received it. Given the passage of time, neither Shaffer nor his assistant had any specific recollection of this letter. The document’s metadata showed that it was created in September 2008 and this date appeared on the letter, but billing records did not reflect a telephone call to the Pecks at that time. Though it was Shaffer’s normal practice to do so, there was simply no way to prove that the letter to the Pecks had been signed, sealed in an envelope, properly addressed, affixed with postage, and placed in the mail.

A malpractice suit was filed against Shaffer. In addition to the factual dispute about Schaffer’s disengagement, the lawsuit involved a “case within a case” with complicated issues of medical causation. The Pecks’ damages were significant and included past medical bills and the projected costs of medical treatment, physical therapy, and speech therapy until Madison turned eighteen. The case continued for almost two years before a settlement was reached.

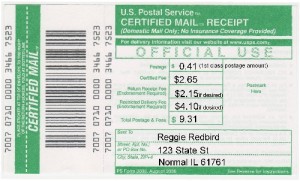

Shaffer has now adopted a system where final, signed copies of all letters (and envelopes) must be placed in the file within seven days after the letter leaves the office. All important correspondence is sent to clients by certified mail, return-receipt requested. Even for an experienced and careful lawyer like Shaffer, these extra steps can make all the difference in avoiding a malpractice claim.

*Names and other identifying details have been changed to maintain confidentiality.

All opinions, advice, and experiences of guest bloggers/columnists are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions, practices or experiences of Solo Practice University®.

Making sure letters are not only mailed but delivered is vitally important. I doubt they teach important but mundane stuff in law school. It is much like a physician ordering a test and then failing to follow up to see if was completed or read the report if it is. My firm routinely calendars outgoing letters of this importance to check on whether they did go out and were received. This is getting more problematic with the Postal Service, as it often fails to obtain signatures or input tracking information. Signatures and tracking need to actually be obtained, preserved, or really what is the purpose of sending registered and certified mail, or overnight packages.

Chuck, thank you for sharing your firm’s practice. I agree that (accurate, meaningful) confirmation of delivery is critical in many instances. Without reminders and checks in place, it is too easy for important items to get lost in the shuffle.